I’ve found that when I travel I’m drawn to certain themes and narratives. When I was working in software the themes were often around how projects came about. In software, a big project is usually completed through a series of smaller projects that can involve multiple teams and stages toward the desired end. How that comes about can be quite complicated and is part of why I found my job interesting.

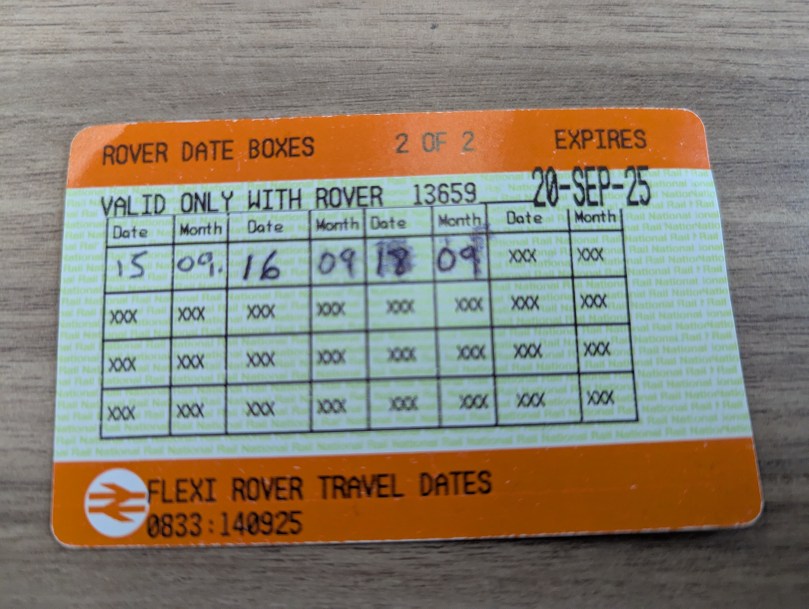

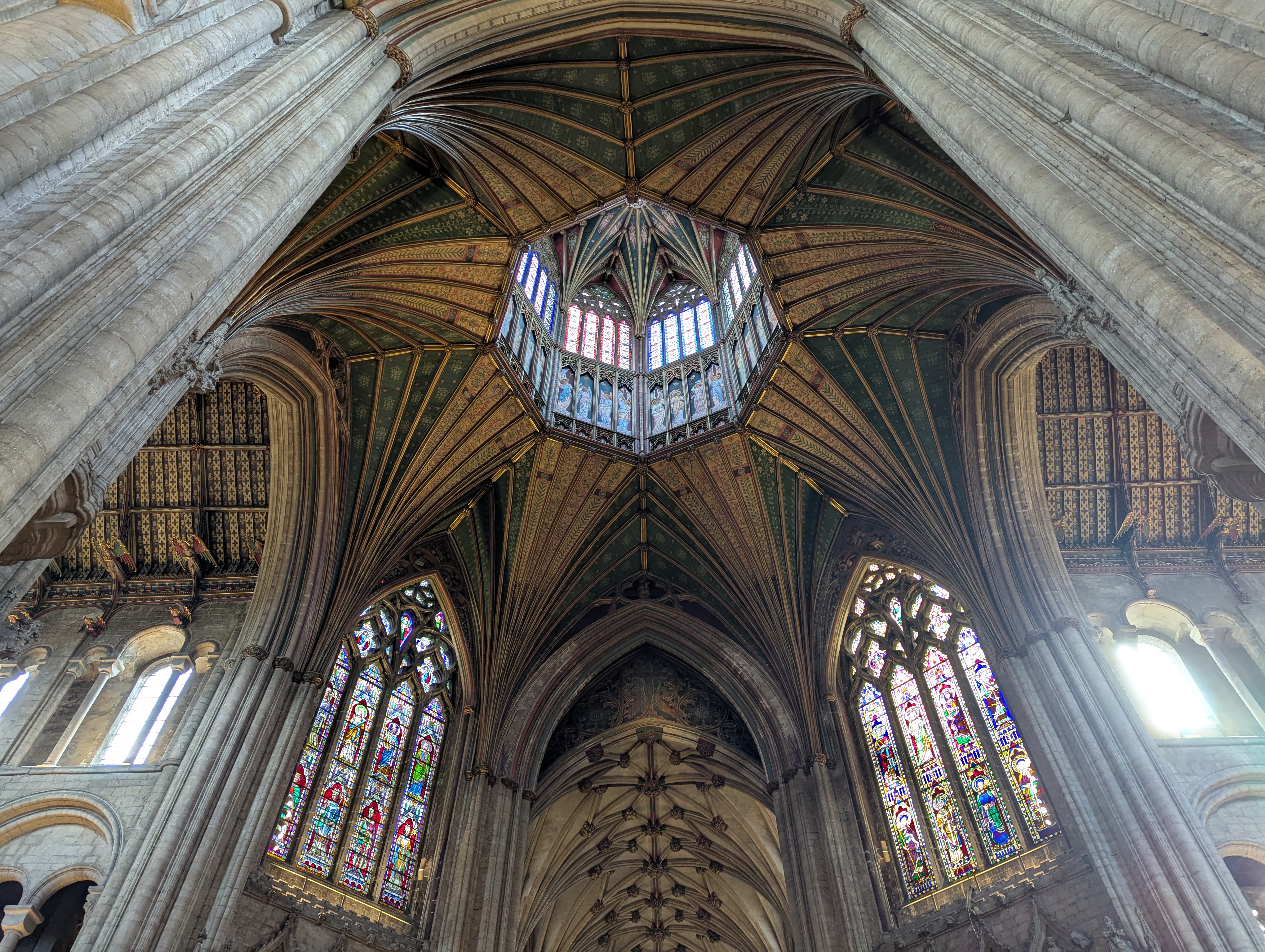

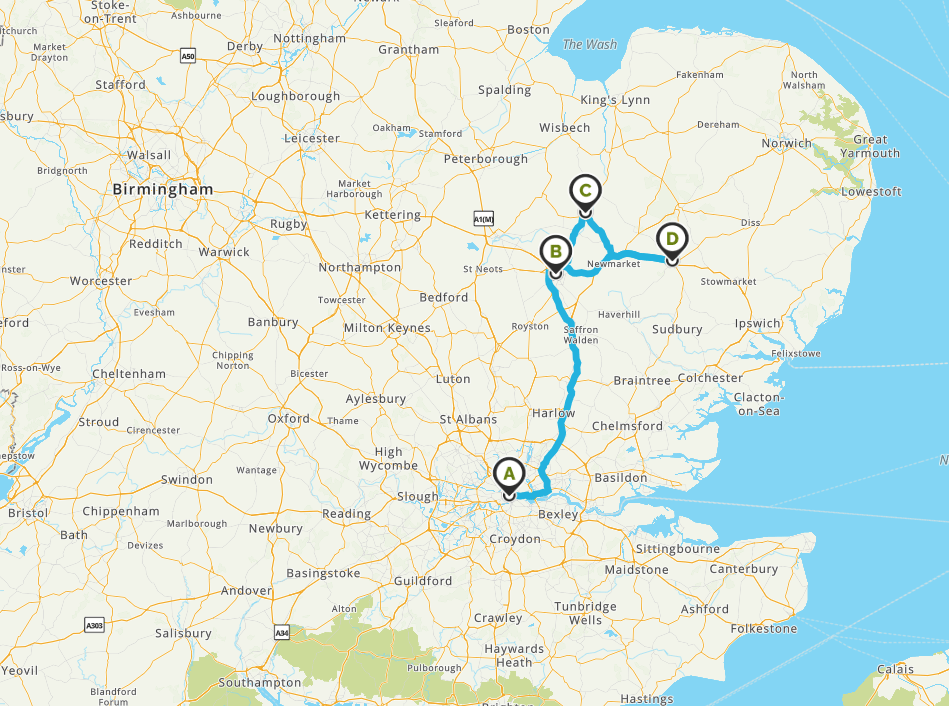

So while traveling and touring I’m drawn to the project aspect of anything. Last week, I was at the Gustave Caillebotte exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago and especially enjoyed looking at the methodology for completing his projects, how his trial sketches were a key part of the process of producing the final painting. I remember touring the iconic Sydney Opera house years ago and learning that the design for the Opera house was based on an artist’s rendering. After it won a competition, architects had to figure out how to build it somehow. It was a project in which there was a tremendous amount of trial and error toward producing the artist’s vision. Kind of the original Agile project. In this trip around East Anglia, one of my favorite parts of the audio tour for the Ely Cathedral was a representation of the stages of building across close to a thousand years. Every hundred years or so a big project would happen. What made me laugh when reviewing the time lapse representation of the build timeline was the times they would add something in one century that in the next century they would remove. Human nature. One man’s innovation is another man’s mistake.

In this trip, one of the themes that was present in my mind was the impact of women across East Anglia. Don’t get me wrong: history always includes the stories of men, and in our touring of cathedrals and museums there were plenty of male historical figures of note. But the history of East Anglia introduced me to several interesting and notable female figures.

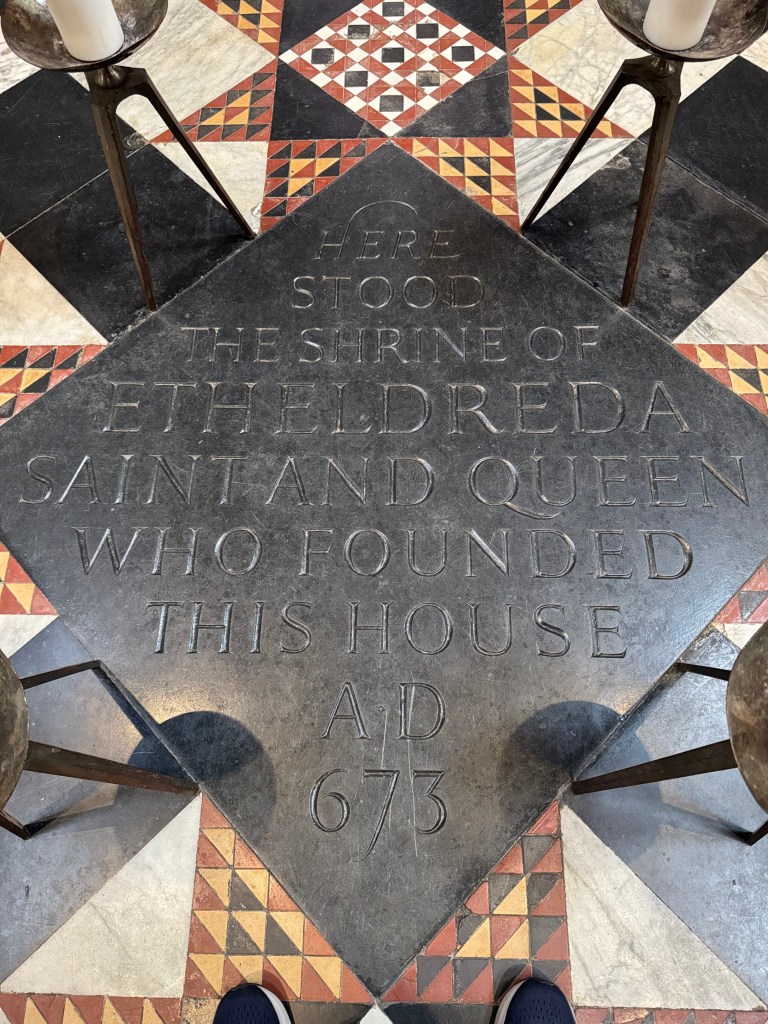

The first one was Etheldredra, important in Ely. Ultimately, she became the founder and abbess for a monastery in Ely in the 7th century, the land on which The Ely Cathedral was later built. But before that she was a king’s daughter and was married off to an elderly king. The audio guide at the cathedral tells us that her husband died before they could consummate the marriage. It says she married a second time, different king, and was released from that marriage since she was still a virgin.

A lot to take in and it made me curious. For one, when I heard about the first marriage in the audio guide, I had the impression that the first husband must have died quickly after the marriage. But other sources indicated they were married for several years. Some sources claim that the deal that was made prior to both marriages–which had been political in nature–that she would be permitted to remain a virgin.

Apparently her second husband came to regret that deal many years in, which led to the marriage being dissolved.

To doubly prove that she really, really was a virgin at the end of that marriage, the audio guide tells a story of her walking stick sprouting leaves overnight.

Interesting that it was an acceptable deal in both marriages that she would remain a virgin when the marriage was presumably for political reasons. The tale of Henry VIII communicates that producing an heir–about 900 years later–is a very big expectation for a royal wife. A lot must have changed in the ensuing years.

Anyway, by today’s standards, kind of a weird origin story for a woman who ended up doing something very, very important when she was allowed to stop getting married off and fulfil her longtime dream of starting an abbey. As an abbess she was highly influential and successful, both in life and after her death, after which she was officially sainted.

The buildings Etheldreda was part of building were destroyed and rebuilt in subsequent centuries. The Ely Cathedral was built on the land starting about 300 years after Etheldreda died. Coincidentally, the monastery at Ely–by then a Benedictine monastery–was closed down by Henry VIII himself.

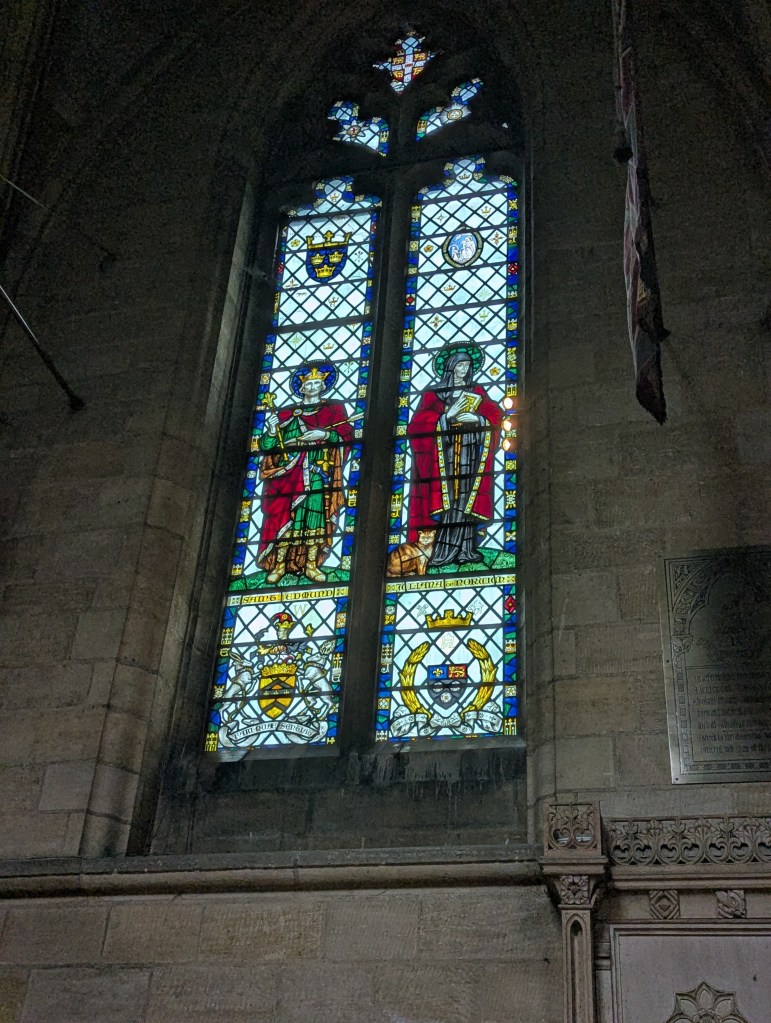

Another woman we became re-acquainted with in Norwich was the mystic and theologian referred to as Julian of Norwich. We had encountered some of her writings when we visited the British Library exhibit Medieval Women: In Their Own Words a few months ago. In the 14th century, Julian wrote the first English language book known to have been written by a woman. Very little is known about Julian, including whether Julian is even her name. She was an anchoress–a religious devotee who lives in a cell–in St. Julian’s church, and her understood name may have come from the church itself. She was inspired to write two versions of a book titled Revelations of Divine Love following an illness in which she was close to death and experienced visions relating to Christ’s death. The first version was written shortly after she recovered from the illness and the second one, much longer, after many years of intellectual and spiritual exploration. Her manuscripts were preserved for 200 years before being published. Although she claims in her writings to be uneducated, her work continues to inspire theologians even in our time. Famously, she posited that God is much like a mother. Our guide at the Norwich Cathedral quoted some famous words of the book that she found comfort in: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.” Julian is commemorated in stained glass in the Norwich Cathedral we visited. Note in the picture the woman on the right pane carrying a book.

Moving on many years, we quasi-encountered Edith Cavell who was born at the end of the 19th century. As we were walking for the first time from the Norwich train station to The Maids Head I saw a pub named The Edith Cavell. Then once we checked in to The Maid’s Head, on the way to our room, there was a meeting room labeled The Edith Cavell Room. I asked myself “who is this Edith Cavell?” She sounded familiar but I couldn’t remember why. It turns out she was the daughter of Norwich-area clergy and had an increasingly interesting nursing career that presumably started either because experienced a failed romantic relation OR because she helped her father through a serious illness. Or both. Her nursing took her into teaching and administration and allowed extended travel in Europe. She was notable as a nurse in the first World War for treating war wounded from both sides but ended up running afoul of the Germans for aiding the escape of more than 200 soldiers from Belgium. She admitted her “guilt” and was executed at age 49 by a German firing squad. She showed virtually no fear leading up to her death, glad to die for her country and with her soul at peace. Her body is buried outside the Norwich Cathedral.

And finally, we encountered Edith Pretty, the woman responsible for sharing the Anglo-Saxon treasure of Sutton Hoo with the world in the mid 20th century. Born into a wealthy family, she became deeply interested in archeology and, with her husband, purchased the Sutton Hoo property on which the burial mounds were located. (Interesting side note: before her marriage she, too, was a nurse and served in Belgium in the first World War.) Although many people believed the mounds had already been robbed, as indeed they had been, she was convinced that they contained additional treasure. After her husband passed away, she hired a local excavator, Basil Brown, to explore the site further. He is often credited with the find, as he should be, but the excavation occurred only because she was willing to invest toward the work. She waited patiently for the coroner inquest that would rule on who had rights to the treasures, rejected rewards from the crown for gifting the property, and as soon as it was clear it was hers to dispose of as she wished, she donated all artifacts to the British Museum to add to our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon culture and be enjoyed by everyone. Like our other women, Edith Pretty was a Boss.

It occurred to me that every one of these women became known for what she did when she was single, regardless of how she came to be that way. Perhaps being single contributed to their being able to pursue a deep-seated interest given the times in which they lived. You have to admit we are looking at a very long period, more than 1000 years, in which it seems true that it has been quite difficult for a married woman to pursue the kind of work that speaks to them as a person, unless that work happens to be taking care of family. (I do note that some of these “jobs”–like being in a monastery–just require being single.)

To be clear, we know about these women because they became famous. In my mind, fame is not the object for most of us. The object is being able to do work that interests one greatly.

And as much as I note that women have made progress since Edith Pretty’s death in the 1940s, it seems there are still forces that hold us back. In fact, forces that existed in the past that were briefly weakened seem lately to be coming to greater strength.

Ominously, women leaving the workforce at high rates. Although unexplained, some factors believed to be involved include rapidly increasing cost of child care and the newly growing wage gap between men and women workers. Removal of women from government positions under a new regime, where the claim is that they are insufficiently qualified. And my social media feeds over the summer included a video in which a well-known male operative, leading seminars for young women, encouraged them not to work or attend college. Or if they attended college not too work hard at it. Ok to pursue “an MRS degree,” where you are only attending college to meet eligible bachelors. Indeed, ready yourself for a life of servitude where you take care of family and be subservient to your husband, the boss of your family. Sorry for the bad luck of the accident of your gender.

As a recent retiree from a job I loved I’m so thankful for the period in time in which it’s been possible as a woman to pursue interesting work. My fervent hope for all women is that one is not required to be single or childless to be able to freely choose and grow in an occupation. That women be judged on their objective merits instead of assumptions about people of your gender. That when partnered, their partners support their self-actualization, just as they support the same in their partners.

I bet all the single ladies of East Anglia agree.